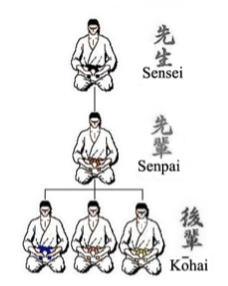

In recent times I have been given the title of Senpai in my Dojo, having become the student with the highest grade. I feel the role is one of responsibility, and I try to assist my Sensei in the Dojo, support the group by whatever means necessary and to lead by example, in all things ‘Budo’. But what exactly does the role entail? What does the term mean? And why does it exist? Like many Japanese terms we adopt in our study of martial arts, we have our own western ideas, but with little understanding as to the real values it holds in Japanese society.

Senpai is pronounced as ‘Sempai’, and the literal translation in Japanese is senior. The term is often applied in school, business, the arts, and of course, the martial ways and refers to a senior or early member of a group. The meaning, however, for those in a traditional martial arts group and in Japanese society as a whole is much deeper.

The Senpai tradition has existed since the beginning of Japanese history, but the role cannot be fully understood in isolation. It is the Senpai – Kohai relationship that we should consider, Kohai meaning junior or later member. This system employs a method called On-‐Giri, meaning deputy or obligation. The Kohai has a certain debt which is owed to his Senpai by virtue of their willingness to impart knowledge. This relationship of a vertical hierarchy in Japan was primarily evolved from three main factors; Confucianism, the Japanese family system and the Civil Code of 1898.

Confucianism came from China between the 6 th and 9 th centuries, and its teachings of loyalty and respect for elders were well accepted by the Japanese. At this time, loyalty was taken as loyalty to a feudal lord or the Emperor. In the Japanese family system, the father, as the male head of the household, had absolute power over the family and the eldest son inherited the family property. Because of this, reverence for superior, or elders was considered a virtue and from the earliest age a Japanese citizen was indoctrinated into these attitudes. The Civil Code of 1898 further strengthened the rules of privilege of seniority and reinforced the traditional family system, giving clear definitions of hierarchical values. This was called Koshusei, meaning family-‐head system, giving the head of the household the right to command his family, with the eldest son due to inherit the position. This tiered family system can still be seen in other cultures, such as the British Royal family, for example, where the eldest son is the natural heir to the throne. In Japanese society, however, this attitude is deeply ingrained into the culture. The code was abolished after the Second World War, when many things changed, but, by then had played a key role in shaping relationships in Japanese society.

In the Japan of today, the Senpai – Kohai relationship applies to great extent in junior and senior high schools, where older students have great powers and influence over their younger pupils. The seniority system is also a cornerstone in interpersonal relations within the Japanese business world. For example, at meetings the lower-‐level employee should sit in the seat closest to the door, while the senior employee sits next to an important guest. The terms of kamiza and shimoza are used in describing the layout of the board room, in a similar fashion to that of the dojo. Most Japanese people, even those who are critical of it, accept the senpai – kohai system as a common sense aspect of society.

The position that we, as martial artists are familiar with was prevalent in the Japanese Samurai and Okinawan Warrior Society as far back as records go. Originally Senpai was the most senior warrior in a group, under the group’s commander or leader. The Senpai was responsible for development and direction of the lower warriors, and, critically for protection of the leader. No other position in a warrior group had these responsibilities.

As time progressed, the role remained very much the same in Japanese martial arts, with Senpai sitting between Sensei and Kohai in the hierarchy of a martial arts dojo. Senpai would maintain the relationship between Sensei and the students. But the role could be a turbulent one, with Senpai constantly observing the Kohai with an element of distrust as to who may be looking to replace them in a power struggle.

As the senior member of the dojo, Senpai had trained under Sensei for many years. This developed an understanding of Sensei, their training methodologies and philosophies. There is, after all, more than a little of the art itself residing in the personality of the teacher. With this relationship, that was often more personal than others in the dojo, came trust from Sensei, reciprocated by responsibility from Senpai. With these privileges, Senpai had the sole responsibility of protecting Sensei with his life. In times of war, depending on the skill and strength, Senpai could either be the strongest or the weakest link in the command chain. A Senpei who was not the strongest, was therefore quickly replaced, out of necessity to survive. In today’s society, and in particular Western Dojo’s the Senpai role has been diluted somewhat. You may find that the actual expectations and responsibilities in any particular school, differ from similar roles in Japanese dojos, but the title of Senpai still retains its essence in commitment to Sensei, the Dojo and responsibility for promoting the art and culture of Japanese and Okinawan Budo.

Within the dojo, Senpai is predominantly responsible for Kohai etiquette or reigi in Japanese. Senpai means that you are personally accountable for the training of your Kohai in reigi, and this is a key part of the role. If Sensei deems students to be lacking in this discipline, it is Senpai who is to blame. In this respect the Senpai of the dojo, is parallel to the role of Senpai in other aspects of Japanese society, as discussed earlier. As in business for example, some line managers are held responsible, not solely for their subordinate’s work, but also for their behaviour on a personal level and the manner in which they conduct themselves out side of work. In Western society, this would cross many ethical boundaries, but echoes the spirit of Japanese culture and its allegiance to the Senpai Kohai system. In the dojo it was Senpai’s responsibility to immediately correct any breach in reigi toward Sensei from his Kohai. Senpai will lead by example in reigi so his kohai can follow. In doing so, Senpai sets and maintains the attitude in the dojo. But there will also be occasions when clear direction is given and even reprimanding of kohai if repeated failure to follow reigi occurs.

Sensei has the most valued skill and experience to impart knowledge of his art to the students, and the group should therefore cherish Sensei’s time. The delegation of responsibility for reigi to Senpai, means that more time can be dedicated to developing the art through Sensei’s teaching. Much of what martial arts teaches us, extends beyond the mere practice of the skills and develops our values. The teachings that are delivered in the true spirit of martial arts will help us to grow in confidence and stature, but to maintain humble thoughts and a culture of respect. This is another reason why Senpai is often called upon to deliver correct etiquette. While Sensei should and rightly does command respect, it could be seen as egotistical for Sensei to demand this respect on his own behalf, and so Senpai is there for guidance. Whenever I have attended Gasshuku’s in my chosen art, I have witnessed the Senpai remonstrating students for poor etiquette. On this occasion the Senpai was 5 th Dan. This fact alone helps to remind us that regardless of skill and experience, we are all still Senpai with Sensei above us and Kohai beneath, with knowledge to impart and much to learn.

Part of the role, regarding reigi, in a traditional school is for Senpai to order the students to line up for Sensei at the start of class. This should be done as Sensei enters the Dojo, or, when Sensei is already in attendance, that it is obvious to Senpai that Sensei is ready to begin. This shows respect for Sensei in not keeping him waiting, and not wasting any training time. Senpai will align himself at the right of the dojo line. This is where the high grades line up at the high seat or Joseki. Elements of this tradition have crossovers into the board rooms of Japanese business, and most likely other ceremonial events. It is traditional for Senpai to position himself slightly forward of the line and facing at a 45 degree angle, while the Kohai are facing forward, to Kamiza. In ancient times this positioning comes from Senpai’s role as protector of Sensei. He positions himself with this viewpoint to ensure he has a clear view of both Sensei and anyone who would be a potential attacker. While it is unlikely that a loyal student would deem to attack Sensei, there may have been occasions in wartime where enemies may try to infiltrate a dojo for such purposes. Depending on the art, and adherence to tradition, this position may vary slightly. Due to the unlikely threat from students in the modern Dojo, the position of Senpai may be in line with other students, or slightly forward, but facing direct to Kamiza. Senpai also leads the same protocol at the close of training following instruction from Sensei to do so.

During training Senpai will conduct himself as a role model for others in the dojo. This extends to correct performance of reigi, consistently dedicated training and assistance to Sensei in demonstration and teaching where required. As the senior, and most likely, the longest serving student, Senpai has a great deal of experience to pass to his kohai. It is Senpai’s role to tutor Kohai along whenever possible. Often the instruction is not as formal as the Sensei’s; rather it is given by example. Senpai should be positive, kind and display respect in his guidance, thus showing proper budo. The Senpai is acting more like a big brother, rather than the fatherly figure of Senpai. In this respect the role of Senpai is the first of many steps towards becoming Sensei. In return for their guidance Senpai learns new experiences from the Kohai by way of developing a sense of responsibility.

From a Western perspective, the Senpai of the modern dojo is the middle management of business, the big brother of the family and the ally of Sensei. He is a direct reflection of Sensei’s teachings, in the same way as the kohai are of Senpai’s example. From a Japanese viewpoint, the role is steeped in the traditions of loyalty and respect to figure heads and permeates the very fabric of all society. Such relationships are not easily translated or fully applicable in our own Western culture, but are an interesting insight into the culture from which martial arts stem.

Research

‘Being Senpai’ – Internet Article by Kobukai (2014)

‘Senpai vs Sempai’ – Internet Blog.

‘Senpai and Kohai Traditions’ – Internet Article by Dave Lowry

‘Senpai Responsibility’ – Internet Blog (2000)

‘Senpai and Kohai’ – Internet Article by Howard Collins (2013)

‘Okinawan Karate and Kobudo’ – Essays by Mike Jones (2011)

‘In the Dojo’ – Dave Lowry (2006)

‘The Senpai/Kohai relationship’ – Wikipedia.

‘The Heart of the Warrior’ – Catharina Bloomberg (1994)